In order to showcase the work we do in Pattern-Cog, European project funded by ERA PerMed, we caught up with Robert Dahnke from University Hospital of Jena and asked him a few questions about his work, expectations and challenges.

- Please introduce yourself and tell us a bit about the institution you work for

I have been working in the Structural Brain Mapping research group of Prof. Christian Gaser at the University Hospital of Jena for more than 10 years. The University of Jena was founded in the 16th century and has a long tradition in the field of neuroscience, for example with the invention of the electroencephalogram by Hans Berger in 1940 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Jena is a small town in the center of Germany with a strong background in neuroscience.

- What is the focus of your work within the Pattern-Cog project?

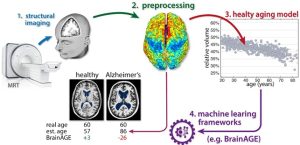

In Pattern-Cog, we contribute our expertise in magnetic resonance data processing and BrainAGE estimation. Our group is working on the development of the Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12), which allows users to analyse the shape and form of brain tissue in development, aging and disease 1. These measures can also be used to estimate the age of a person’s brain 2-3. First, a machine-learning framework is trained on brain data of healthy people, along with their age value. This trained model can then be used to estimate the age of the data of other individuals. The difference between the estimated age and the real chronological age represents the BrainAGE. In healthy people, the BrainAGE is close to zero because their brains age as it is expected for their chronological age. However, in individuals with disease, BrainAGE is often increased, which means that these brains have lost more tissue than expected for their age and therefore appear older (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) can produce images of brain structures that can be used to model the changes of healthy aging. Machine learning frameworks, such as the BrainAGE framework, can be used in various ways to simplify complex brain patterns into values we can more easily understand.

Although brain measures have been successfully applied for research purposes, their use in individual diagnosis is still quite challenging because of their normal variation within the population and because an older appearing brain does not necessarily mean that the person is functionally impaired. Nevertheless, both morphometric and BrainAGE scores could provide clinicians with useful information for diagnosis (Figure 3). Pattern-Cog allows us to improve our understanding of the different measures for their potential use in real clinical applications.

Figure 3: In PatternCog, we look for instance for structural changes quantified by BrainAGE in the ADNI cohort. This is a large cohort of healthy people, individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease patients, who got scanned multiple times. We can observe that people with mild cognitive impairment who later progressed to Alzheimer’s disease have a higher BrainAGE than people who did not develop this disease. Brain pattern indicates the coming progression of the disease even if cognitive tests are still in the group specific range. Moreover, BrainAGE can be also estimated for different brain regions, where some are more affected by neurodegeneration than others, for example, the temporal lobe with the hippocampus shows more tissue atrophy and therefore yields increased BrainAGE values. Taken together, MRI biomarkers can help to improve the prediction of cognitive impairments.

- What do you enjoy the most about your work on the Pattern-Cog project?

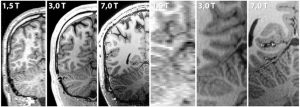

For me, medical imaging is a combination of engineering and art, where processing allows us to look into our heads and observe the beauty of the highly individual shapes and properties of the brain (Figure 4). The constant development of improved imaging and new processing techniques that allow ever more precise and robust measurements (Figure 5), as well as the development of small portable ultra-low-field scanners that allow much cheaper but also less accurate scans, are both challenging and fascinating to me.

Figure 4: The brain is a highly individually folded structure that loses more and more tissue throughout life, as shown here for three left central cortical surfaces of subjects in the IXI dataset.

Figure 5: MR scanners have been greatly improved over time, for example with higher field strengths, which allow more precise but also more expensive imaging.

- What are your expectations and what do you think is the importance of the project for the wider field?

PatternCog represents another step from bench to bedside, helping to understand brain changes in disease and how lifestyle factors influence them. And although the variety of brain shapes makes it difficult to draw individual conclusions, this variability also gives us some sense of freedom and hope that not everything is determined by our genes.

——–

References:

- Gaser, C., Dahnke, R., Thompson, P. M., Kurth, F., Luders, E., & The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2024). CAT: a computational anatomy toolbox for the analysis of structural MRI data. GigaScience, 13, giae049. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giae049

- Gaser, C., Kalc, P., & Cole, J. H. (2024). A perspective on brain-age estimation and its clinical promise. Nature computational science, 4(10), 744–751. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-024-00659-8

- Kalc, P., Dahnke, R., Hoffstaedter, F., Gaser, C., & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2024). BrainAGE: Revisited and reframed machine learning workflow. Human brain mapping, 45(3), e26632. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.26632